%%

The charges brought against the Iuventa crew are related to three different rescue operations. The related allegations are based on extensive undercover investigations that drew in multiple law enforcement agencies overseen by a particular specialized branch of the Italian judiciary: the Sicilian anti-Mafia. The charges are severe and relate to a maximum prison sentence of up to 20 years. The case file amounts to almost 29 thousand pages.

Meanwhile, sea rescuers are not alone in facing charges.

Among them are countless people on the move criminalized for having helped other people on the move in need, or for having been forced to skipper the boats bearing them across the sea to Europe. Greek courts routinely sentence migrant skippers to an average of 44 years in prison and a 370,000-euro fine on the basis of 30-minute hearings. Those people’s stories are rarely told, and their bravery rarely celebrated.

Across Europe and beyond, from Lesvos to Calais, from Tangier to Bardonecchia, from the Roja Valley in France to Denmark, hundreds of men and women stand trial for “crimes of solidarity.” For having offered food, shelter or clothing to people on the move.

Prologue

The history of migration is a history of restrictions on the movement of all but a white wealthy elite. To those with the right passport, the earth appears as a smooth surface whose boundaries few can cross effortlessly. For people with the “wrong” passport, each border carries the threat of violence, exploitation or death.

Change of Command: From Mare Nostrum to Triton

1. Iuventa Mission

Rescue blankets spread out to dry on the deck of the Iuventa

Tipping Point

For years, Europeans had looked on as their politicians transformed the Mediterranean into a mass grave for Europe’s undesirables. In 2015, we heard our leaders publicly mourn the loss of life at sea to which they themselves had contributed. Touting their own enlightened humanitarian principles, they grieved those who had drowned as though their death had been the sad but inevitable consequence of a natural disaster, or of the especially predatory nature of ruthless traffickers. Their hypocrisy was unbearable. Unwilling to look on as people were left to die in the name of protecting our privilege, some of us decided to intervene where our governments had refused to. Ordinary members of civil society began to organize a grassroots response to the catastrophe unfolding in the Mediterranean.

The origins of Iuventa

Like other rescue NGOs, the Iuventa was a direct action with a humanitarian mandate to save life at sea. But unlike many humanitarian organizations, the Iuventa’s project was expressly political. It was rooted both in the broader struggles for mobility that marked the 2015 “long summer of migration” and in the period’s massive and protracted protests against austerity, neoliberalism and the policing of civil society within Europe itself.

These networks, in other words, did not aim solely to vouchsafe the human rights of migrants at sea. They were also attempts to practice and build upon the kind of solidarity from below that would involve migrants and Europeans in a joint project to reimagine a world free of capitalist and imperialist exploitation. For many of us, these mobilizations promised the beginning of something that might change our lives as well.

On Board

Ships have long been spaces of alternative political imaginaries. When the Iuventa set sail on her first mission on 27 July 2016, she was both a powerful tool of direct action and a symbol of opposition to Fortress Europe that harnessed the energy and aspiration of a vast network that bridged older generations of ’68ers or autonomist Marxists and younger Antifa militants bred in the European counter-culture scene, hardened anti-racist radicals and people who had never previously been involved in politics.

For the Iuventa, carrying to sea that militant tradition of directly creating and intervening in politics (rather than looking to institutional channels) meant not only rescuing people on the move, but forging political alliances that could help define a common struggle on land.

Iuventa soon acquired a reputation for that militant spirit and for the lengths to which we were willing to go to save life at sea. We ventured closer to the 12-mile boundary of Libyan territorial waters in order to reach people as soon as they encountered distress. Once there, we took on as many people as our ship could carry.

Over the course of 16 missions, the Iuventa crew assisted 175 boats and was directly involved in the rescue of more than 23,000 people. We took over 9,000 people on board, while providing life jackets and first aid to many others on the water, stabilizing their boats until help arrived. We treated thousands for dehydration, circulatory failure, hypothermia, chemical burns, pregnancy complications, and more.

It was likely our uncompromising approach to rescue, together with our insistence on integrating the practice of rescue with a broader critique of the European institutions that had endangered those lives, that attracted the attention of the Italian authorities.

Crewing

The Iuventa was operated by more than 200 volunteers over the course of its 16 Missions. Volunteering on board involved being at sea for at least 2 weeks as well as intensive days of trainings and briefings to get familiar with the new – for some of us completely unknown – environment. Many spent their annual leave on board the ship. Nobody was paid. Only travel expenses were reimbursed; room and board were provided on Malta and on the ship. Half of the crew were professional sailors; the others had little to no experience at sea but made up crucial non-nautical personnel on board: the deck manager organized crowd management while rescued people were on board; aided by a medic, the doctor on board maintained an overview of the medical condition of both the crew and the people rescued, providing treatment when necessary. Below deck, the engineers operated the ship’s main engine, generators, pumps, compressors, the crane and winches.

“As a long-time political activist I took action in the Central Mediterranean because to me it seemed like the most concrete way to fight against Fortress Europe. Taking that struggle to the Central Mediterranean was only the logical next step to the no border camps.”Hendrik, RIB-Team

“Not even my 20 years of experience as a barge-captain could prepare me for this man-made disaster on the Mediterranean. But as long as I cannot abolish capitalism, it seems obvious to me that the next best thing is to stand in solidarity with those who suffer because of capitalism.”Dariush, Captain

“I am an ICU worker, which has prepared me for the medical care on board, but I’d never been on a ship before. As an activist who believes in the principle of the freedom of movement, it seemed logical to join the Iuventa to stand in solidarity with people on the move”Lea, Medic

Our crews were made up of people from all walks of life, all united by the urgent need to intervene in and change a situation we found unacceptable. We had identified the Central Mediterranean as one of the key fronts of the struggle against injustice and exploitation, and we wanted to make an immediate, material difference in that fight.

Thousands of donors supported the Iuventa’s missions, covering the ship’s maintenance costs, as well as travel, food and accommodation for the crew. Alongside that sponsorship, donors, family, friends and comrades supported us by campaigning against the mass death in the Mediterranean passage in the streets, on university campuses, in churches and in the workplace.

Anatomy of a rescue

The Iuventa’s mission was simple: to save people whenever possible, and to provide shelter when necessary. The concept, which we called “pro-active SAR” was as basic as it was effective. It involved:

- Actively searching for boats in distress, sailing across known migration corridors where distress is most likely to occur, being on call 24/7 and ready to intervene as soon as a distress case arises.

- Securing people in distress as fast as possible with life jackets, life rafts, floating devices and taking as many people on board as possible

- Treating life-threatening injuries

- Identifying exceptionally vulnerable people and treating them accordingly.

- Being ready to improvise.

At the time of our operation there were six basic steps to rescue a boat in distress in the Central Mediterranean:

The Iuventa provided a “temporary place of safety” for people on the move across the Mediterranean passage. But what was threatening to the authorities was not that we saved migrants’ lives, but rather that we made sure that people braving the journey were not returned to Libya. We ensured that they reached the European shores where they could exercise their right to seek asylum in the EU.

Cooperation

Full cooperation with the relevant Maritime Rescue Coordination Center (MRCC) and with all search and rescue units involved in the area is a matter of both principle and necessity for us and is an inherent part of any rescue mission. The Iuventa never deviated from its commitment to complete transparency, full cooperation and total compliance with the instructions of the Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Center (IMRCC).

Who we met at sea

People leave their homes for a number of reasons. Most are forced to migrate because their livelihoods have been destroyed by war, resource exploitation, climate change and unjust economic and trade relations developed over centuries. Each of the people we rescued has a different story. But they have one thing in common: all of them had to confront the brutality of Fortress Europe in order to reach safety. They faced that brutality first in the Mediterranean, and then in the infinite obstacles to legality enshrined in European asylum policy. Today, some of them are not only threatened with deportation, but face criminal proceedings for the simple fact of having migrated.

Here, we introduce three of the people we rescued, and with whom we managed to keep in touch after our first meeting on board the Iuventa.

“I spent 1 month and 4 days in a Libyan prison because I tried to escape from this country... they tortured us, I saw many people shot to death in this prison.”

20 years old, from Sierra Leone. Currently living in Germany. Rescued on 29.07.2016 together with another 696 people in our first rescue operation off the Libyan coast. He left his country because he was a homeless 13 year-old, selling plastic bags on the street to survive.

“It wasn't safe. In Libya, people are raped, tortured and killed. If someone had told me I would be sent back to Libya, I would have preferred to just die at sea.”

31 years old, from Nigeria. Currently living in Italy and waiting for the ruling in his asylum procedure. He was rescued on the 05.10.16 together with other 30 people from a flimsy wooden boat. He had to leave his home after facing political persecution by a militant Islamist group.

“Our journey began at midnight. The sky and the sea were both so dark. I didn't know what to do or where to go.”

30 years old, from Syria, He and his father are living in Germany. He was rescued on the 15.04.2017 together with other 1000 people in a dramatic mass rescue operation. He had to leave his home to escape the war in Syria.

2. Changing Tides

Mass rescue operation on Easter weekend 2017. Photo: Moonbird, Sea-Watch

In 2016, our presence on scene had forced the Italian and EU authorities to do their job: saving people and bringing them to a place of safety. We had also managed to create a working relationship with the Italian Coast Guard (ICG) and the European Naval Force (EUNAVFORMED), under whose coordination we conducted our rescues. But as the year drew to a close, we witnessed the authorities’ increasing efforts to shirk their responsibilities and become evasive in their communications with civil assets. In the Search and Rescue zone itself, this made rescue conditions harder and harder. Our ship was overcrowded as we waited days for a supporting vessel to take our passengers.

Meanwhile, the ships in the SAR began to change. While fewer EU-assets were visible on scene, the so-called Libyan Coast Guard upped its operations, assuming control of rescues or intervening in civil rescue operations in order to hinder the activities of NGOs. Armed Libyan militiamen boarded civil ships and forced them to sail away from the SAR zone.

In spite of these intimidation tactics we and other NGOs managed to stay on scene and continue to help people in need. But though we did not know it then, this was only the beginning of a long strategy of externalization and pushback by proxy that would come to shape the Mediterranean passage to this day.

Shifting tactics

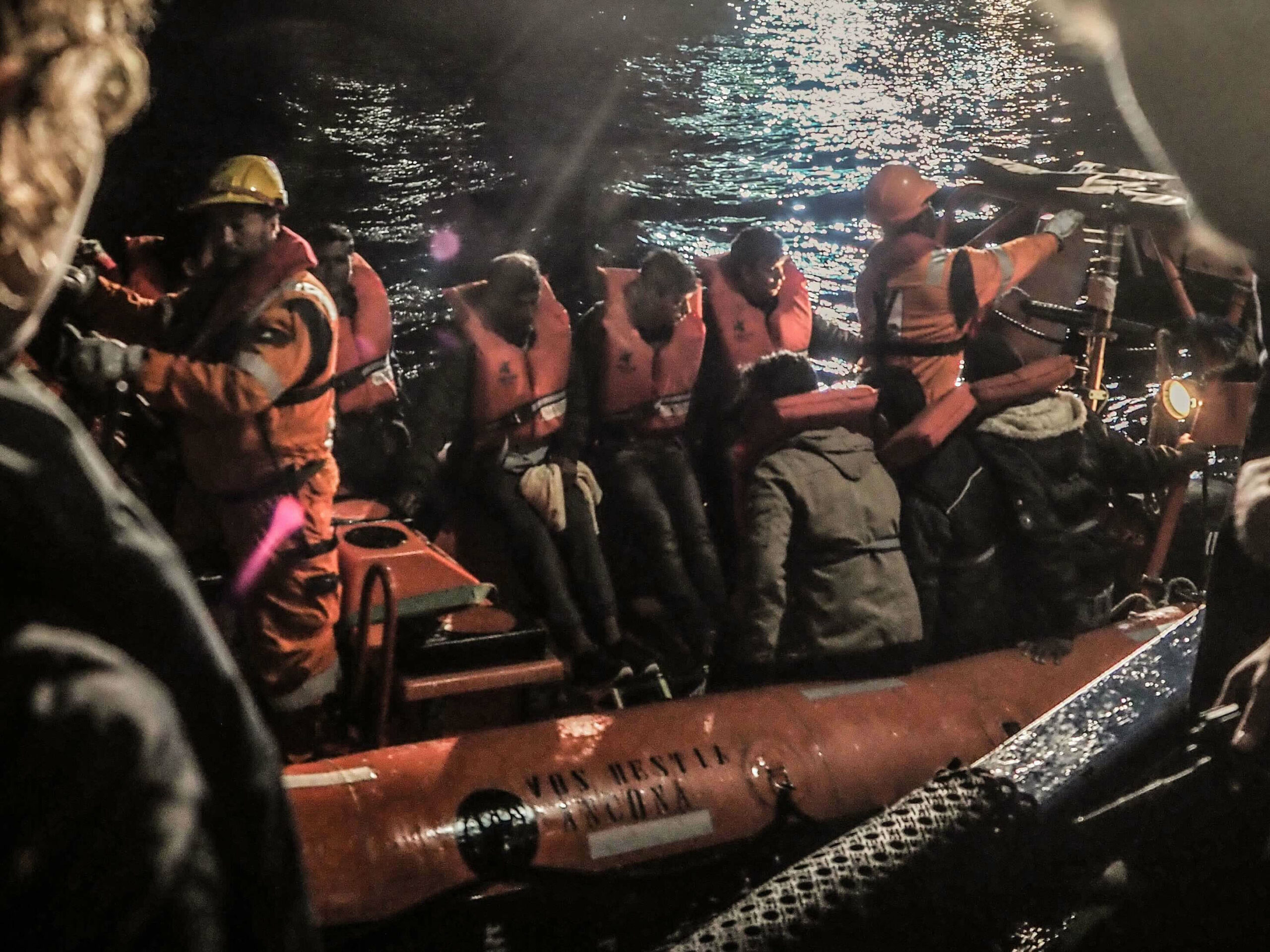

Night transfer of rescued migrants from the Iuventa to the Vos Hestia. Photo: credit: Selene Ena

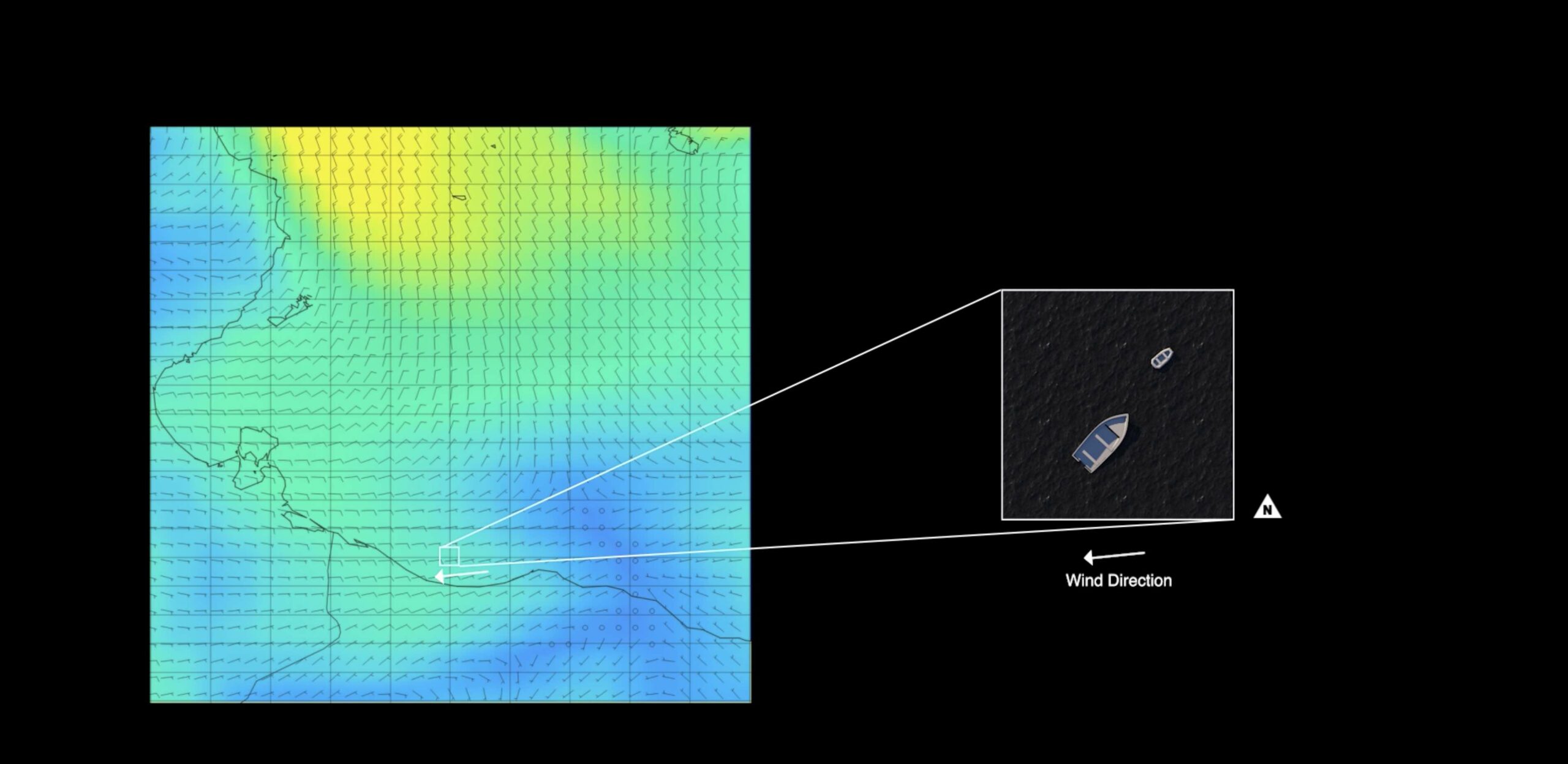

As the EU scaled up its surveillance and policing operations in its alleged fight against traffickers in the Central Mediterranean, smugglers were forced to change their own behavior. This involved:

- a reduction in fuel, in the food and water provided; an increase in departures under more difficult weather conditions;

- an ever higher number of people on board;

- a tactic of sending out many boats at once, which led to increasing instances of “mass rescue”, where over twenty SAR cases presented themselves simultaneously.

The Iuventa regularly faced such incidents. During the Easter weekend of 2017, the crew were forced to launch a May Day call after being left on our own for hours to tend to 12 to 14 boats in distress.

It was in this period of dramatic shifts in the balance of power and in tactics of policing and evasion in the Mediterranean that NGOs emerged as a new target for European authorities.

The criminalisation of sea rescue

It is difficult to attribute the criminalization of sea rescue to any one political actor or motive. From think-tanks to the governing EU and Italian establishment, from the anti-Mafia to rising populist movements, from FRONTEX to the alt-right, each had a vested interest in destroying the reputation of sea rescue NGOs and preventing them from operating in the Mediterranean passage.

3. Under Investigation

The Vos Hestia during a joint rescue in September 2016; one of the informations, Pietro Gallo, sits in the bow of her RIB

The investigators

State efforts to police our operations did not begin with the Minniti code. Though we did not know it, the civil fleet had, since even before the attack launched by GEFIRA, been at the center of extensive undercover investigations that drew in multiple law enforcement agencies overseen by a particular specialized branch of the Italian judiciary: the Sicilian anti-Mafia.

Today, the anti-Mafia hold jurisdiction over the gateways of Europe, at the intersection of national and European borders and of the transnational apparatuses of migration management, border enforcement and humanitarianism. In the wake of the Arab Spring and increased migration across the Mediterranean, anti-Mafia judges and investigative units began to repurpose the skills they had developed to police the Sicilian Mafia. Claiming more general expertise in tackling transnational organized crime, they used that skillset to investigate the transnational operations of trafficking drugs, weapons, oil and people, across the Mediterranean. These investigations, known as the Glauco Operations, relied on the capture of suspected traffickers at sea and their coercion into turning state witnesses. Dozens of arrests were made on the basis of a single witness or pentito. The approach led to a number of policing disasters, such as the recent case of mistaken identity that saw an innocent man misidentified and charged as a human trafficking kingpin, Medhanie Mered.

The recent history of Anti-Mafia investigatory practices provides one further important insight into the institutional motives behind the prosecution of NGOs. In March 2017, Carmelo Zuccaro, a Sicilian prosecutor, explained to a Parliamentary Committee on migration that since NGOs had begun to operate in the Search and Rescue zone offshore Libya, it had become much more difficult for anti-Mafia teams to conduct their investigations into trafficking cartels by capturing suspected traffickers. What is more, the NGOs were unwilling to take on a policing role for the Italian authorities. Without meaning to, rescue NGOs had compromised a massive and costly transnational policing operation in the lurch.

It was not by chance that in the same hearing Zuccaro requested that the government allocate more funds and personnel to a recently launched police operation focused specifically on the activities of the NGOs.

The dossier

Because they were conducted by the policing and judicial apparatus of the anti-Mafia, much of the information surrounding investigations into NGOs is classified. While we know that in May and June 2017, separate investigations into Iuventa, Sea-Watch and Proactiva, were carried out by at least 3 different judiciaries, the Iuventa’s is the only public police file from the period. The dossier allows us to reconstruct the policing tactics that went into our arrest and, with that, the interlocking interests of the Italian state, the EU and the rising right wing.

The informants

In September 2016, 12 NGO ships were operative in the Search and Rescue zone. Among them was the Vos Hestia, a ship chartered by Save the Children and operated by a mix of humanitarian personnel, subcontracted crew and security agents employed through a small private security firm, IMI. Though no one knew it at the time, IMI’s founder, Christian Ricci, had ties to the Generation Identity movement, while the agents on board were supporters of italian right-wing politicians.

Three of those agents, Floriana Ballestra, Pietro Gallo and Lucio Montanino, launched the investigation into the Iuventa. On September 25th, they sent an e-mail to AISE (Italian secret services) claiming to have evidence of possible collusion between the Iuventa and people smugglers. While the agents never received a reply from the Italian Secret Service, they also reached out to Matteo Salvini himself. He replied instantly. During their next deployment in the Search and Rescue zone, the agents gave the most powerful right-wing voice in Italy a direct line of insight into the heart of the civil fleet. Two and a half years later, in January 2019, a repentant Pietro Gallo voiced his regret for having been Salvini’s spy, and implied that he had been bribed with a promise of a job. He also admitted that he had no evidence of a relationship between NGOs and smugglers.

On October 14th 2016, after they had returned from their deployment, the agents filed an official complaint to the Trapani judiciary, placing the Iuventa at the center of a year-long investigation that drew in multiple law enforcement agencies, including the SCO, an investigative branch of the Italian police specialized in organized crime. Over the course of the following months, the investigative team allocated enormous resources to the case, including wiretaps, bugs and an undercover agent.

Police tactics

In some cases, the investigators’ policing tactics cost lives. On May 4th 2017, the weather was fair offshore Libya, and people were taking the opportunity to brave the crossing. A constant stream of distress calls came out of the rescue zone. Under the coordination of the MRCC, we had crowded hundreds of people onto our deck and were waiting to trans-ship them onto larger ships that could take them to a place of safety in Italy. But the MRCC had other plans. Having instructed us to trans-ship almost all of our passengers, they insisted that we keep five people on board and sail them the day’s journey to Lampedusa ourselves. Even as we protested that we could not guarantee the safety of the people on board and that we were urgently needed in the Search and Rescue zone, the MRCC threatened retaliation if we did not comply. It is likely that hundreds of lives were lost as a result of the MRCC’s strange demand that we remove our ship from the rescue zone on one of the busiest days at sea.

It would be months before we discovered the MRCC’s real motives. While the ship was in port in Lampedusa and the crew interrogated, police investigators boarded the ship and bugged the bridge. The recordings from that bug, together with the wiretaps of crewmembers’ phones, make up a large portion of the police dossier against us.

Two weeks later, the police brokered a deal with IMI security services, the employer of the three security agents behind the investigation. They agreed to plant an undercover operative, Luca Bracco on board Save the Children’s Vos Hestia disguised as security personnel. The agent’s observations of the Iuventa’s rescue from the deck of Vos Hestia provided the bulk of the allegedly forensic evidence against the crew.

Seizure

Seizure in the port of Lampedusa on 02.08.2017

In August 2017, the MRCC sent us on a similar wild goose chase when they instructed us to assist a small dinghy in international waters off the coast of Libya. We moved to the coordinates immediately, but when we arrived, an Italian Coast Guard ship had already completed the rescue.

A very rare case for the Mediterranean crossing, the dinghy had only two passengers, both Syrian. We were instructed to take them on board and steer course towards Italy in order to allow the Coast Guard ship to continue patrolling the Search and Rescue zone for more boats in distress. We agreed, expecting to rendez-vous with another north-bound vessel and pass the rescued men on to them so that we could return to the Search and Rescue zone. This would have been in keeping with standard protocols. And yet every vessel we asked for assistance along the way offered some unlikely justification for refusing the trans-shipment. After four days of waiting for a transfer, the Iuventa was sent on another search, this time of a boat in distress south of Lampedusa.

No official case number was assigned to the boat, as is standard protocol. We searched anyway. Moonbird, a reconnaissance aircraft operated by Sea Watch and the Humanitarian Pilots Initiative, offered to join the search. Though the plane could have covered the search area in a matter of hours, the IMRCC refused the offer. This left us no choice but to follow the search track northwards, towards Lampedusa. By the time the IMRCC cancelled the search we were already a few miles away from the island. We requested and were refused a rendez-vous with a Coast Guard launch to collect our passengers. As soon as we crossed into territorial waters, we saw why. We had sailed straight into an ambush. Five Italian vessels surrounded us ordering us to enter port. In retrospect, it seems likely that both distress cases announced by the MRCC were fabricated in order to force us into port. The next morning, the authorities searched our ship for weapons (they found none) and issued us with a warrant for the seizure of the Iuventa together with a 150-page indictment for collusion with smugglers.

The indictment

The case for the Iuventa’s seizure rest on reports of three incidents. The first, reported by the IMI Security Agents, launched the investigations into the Iuventa’s operations. The other two emerged from an undercover mission conducted by agent Luca Bracco, planted on board the Vos Hestia as a member of IMI Security personnel. They concern two separate SAR episodes, both on June 18th, 2017. The counter-forensics report offers a detailed reconstruction of those incidents.

The majority of the police dossier, however, does not concern those instances in which the Iuventa purportedly broke the law. Rather, it comprises “supporting evidence” harvested from intercepted phone calls and audio transcriptions from the bug planted on the ship’s bridge in May 2017. In part, these serve to outline the Iuventa’s alleged hostility to the authority of the MRCC, its reluctance to report suspected smugglers to the police, the crew’s purported recklessness in approaching or entering Libyan territorial waters – political commitments or operational practices purportedly aggravating suspicions of malpractice. But many of the enclosed transcriptions also offer the lengthy, and often inchoate political opinions of the IMI security staff (answerable to Matteo Salvini) and choice snippets from the crew’s conversations on bridge watches concerning their leftist political origins, belief and practices. The inclusion of these conversations, and the investigator’s concern with them, suggest that what was being investigated was not only the alleged offenses of a single crew in a singular instance, but a political world of the radical Left.

4. Epilogue

Rescued on board the Iuventa; dinghy debris burning in the background Photo: Cesar Dezfuli

The case of the Iuventa marked the peak of an ongoing battle for the Mediterranean waged between, on the one hand, instruments of deterrence, policing and exploitation and on the other, the autonomy of migration and the worlds of solidarity that it inspired. The Iuventa was the first ship to be impounded; its case has lasted the longest. Over the course of the past few years, the authorities have partially achieved their goal of draining the Mediterranean of its rescue assets through a series of judicial and legislative measures and intimidation tactics. It is impossible to estimate how many people have drowned or been returned to the hell of Libya’s detention centers as a result of those measures.

Despite those efforts to dismantle the civil fleet, the Rescue Wars are not over. For as long as people on the move continue to brave the perilous crossing against all odds, the civil fleet will find a way to sail their ships out to meet them. Even as our vessels are impounded and our sailors persecuted, others doggedly find their way out of port to the SAR zone. That struggle continues.

Meanwhile, we sea rescuers are not alone in facing charges for “crimes of solidarity.” Across Europe and beyond, from Lesvos to Calais, from Tangier to Bardonecchia, from the Roja Valley in France to Denmark, hundreds of men and women stand trial for having offered food, shelter or clothing to migrants. Among us are countless migrants criminalized for having helped other migrants in need, or for having been forced to skipper the boats bearing them across the sea to Europe. Greek courts routinely sentence migrant skippers to an average of 44 years in prison and a 370,000-euro fine on the basis of 30-minute hearings. Those people’s stories are rarely told, and their their bravery rarely celebrated.

Even as some of us white rescuers have been lauded for our humanitarianism, we want to be clear that none of us who have stood in solidarity with migrants have done so out of selfless heroism. We are aware of our privilege and, relatedly, responsibility, as white people in a global society build upon the colonization, exploitation and racialization of people of color. Our case cannot be fully understood outside of that context of systemic racism, of which the border is merely one iteration. But we have also acted in the knowledge that those in power test their instruments of domination on their weakest members of society first; they extend them to the rest of us later. Politicians who target, scapegoat and exploit migrants, do so to shore up a violent, unequal world that disempowers us as well. The criminalizing of solidarity aims to foreclose the forms of recognition and alliance that that realization entails. It betrays European leaders’ terror of what might happen if their own citizens and migrants made common cause against Fortress Europe, and exposed it for what it is: a system that robs each of us of our freedoms, security and right to a future without exploitation. In our struggle to preserve our bonds of solidarity is the dogged belief that those systems of domination can be transcended, and a different world imagined if, and only if, we fight alongside each other.

Text by Chloe Haralambous

“